Women In Translation Month 2023: Part 1

I’m not entirely sure where the idea of Women In Translation Month originated but across bookish social media spaces, August is set aside to highlight and read books in translation. Either written by women or translated by them (or both if possible).

I’ve chosen a few books from my shelves to read this month, which I’ll tell you about shortly but first I wanted to look at why this is important and then recommend three books that I have read and loved that work for this initiative.

Does it matter whether a man or a woman translates the work?

If you don’t want to read about the theories and my thoughts on this then you can skip to the end of the post where I have left my three book recommendations and listed the books that I’m hoping to read this month myself.

An interesting question to ask yourself is how different would a translation of the Greek and Norse myths be when completed by a woman over a man? We are talking about translations over retellings, so assuming that the translator feels they are providing a true translation of the original text. Let’s take it one step further, how would the translation be different if completed by a women subscribing to right-wing politics over left-wing politics? Or a devout Christian woman over an atheist?

Earlier this year I prepared an essay in which I began to look into translation theory. An area I had never learned about before but which has opened my eyes to the complexity and nuances involved in translation work.

What I’m sharing here is an extract from a larger essay which I delivered via podcast (it was for a media module). Because part of the assignment was to make it feel like a podcast script, I hope this reads a little more ‘friendly’ than a traditional essay (I got a good mark for it at least!).

Please note this was an essay in which I was examining Roland Barthes essay The Death of the Author, hence references later on in this extract, I will include the bibliography at the very end of this blog post if you are interested.

Let’s turn to the act of translation because this really complicates arguments over the importance of the author, by adding in the translator.

To kick us off I wanted to share the following quote from translator Deborah Smith who has won awards for her translations from Korean into English:

“[Korean] has peculiarities as a language. It’s a subject-object-verb language, so a lot of information is delayed until the end of a sentence: Korean writers will often use that to build tension… What’s more difficult is its reliance on ambiguity and repetition. Repeating words in English doesn’t give you the same poetic effect as in Korean … That just doesn’t work for an English reader.” (Cooke, 2016)

This gives a good introduction to the complexity and intricacies that are present in translating from one language to another. It is not as simple as translating the words in a sentence. A translator must consider the creative and stylistic choices made by the author and determine whether they translate as concepts into the target language, and this adds an ethical conundrum over the veracity of changing the decisions made by the author.

One translation theorist, Lawrence Venuti, is interested in the role of the translator. In his introduction to the book Rethinking Translation: Discourse, Subjectivity, Ideology he begins by looking at how translators are categorised in law and explains that:

“Both British and American law define translation as a second-order product, an ‘adaptation’ or ‘derivative work’ based on an original work of authorship,’” (Venuti, 2019, p.2)

And he goes on to discuss how translations are judged to be a success, through the idea of the “vanishing act”:

“A translated text is judged successful - by most editors, publishers, reviewers, readers, by translators themselves … when it gives the appearance that it is not translated, that it is the original, transparently reflecting the foreign author’s personality or intentions.” (Venuti, 2019, p.4)

The vanishing act hides the amount of work required to produce such an effect, as alluded to with Deborah Smith’s interview in The Guardian.

Venuti goes on to say that a translation deserves to be studied in its own right and

“engaged in questions of language, discourse, and subjectivity, while articulating [its] relations to cultural difference, ideological contradiction, and social conflict.” (Venuti, 2019, p.6)

If we are saying that a good translation is one in which we cannot tell that it has even been translated, then within Barthes ideas of the irrelevance of the author we could determine that it does not matter in which culture a story is created because all that matters is the reader interpretation of the words.

The issue that this perpetuates is appropriation by dominant cultures. If translated works are translated in such a way as to make them ‘palatable’ to western readers, then without acknowledging the author and the act of translation, we are appropriating the stories of another culture. Walker, in talking about the ways in which men’s voices have been used as normative, provides us with Toril Moi’s phrase “the ventriloquism of patriarchy” (Walker, 1991, p.113) which I feel we can extend to ‘the ventriloquism of Western Capitalist Patriarchy’ to cover the domination of Western voices.

And so we see that who translates, why and, from and to which languages is important to look at. In this essay I was not looking at female translators but hopefully you can see how the principles mentioned apply in this context.

Book Recommendations

So here we have my current favourite three books in translation from women.

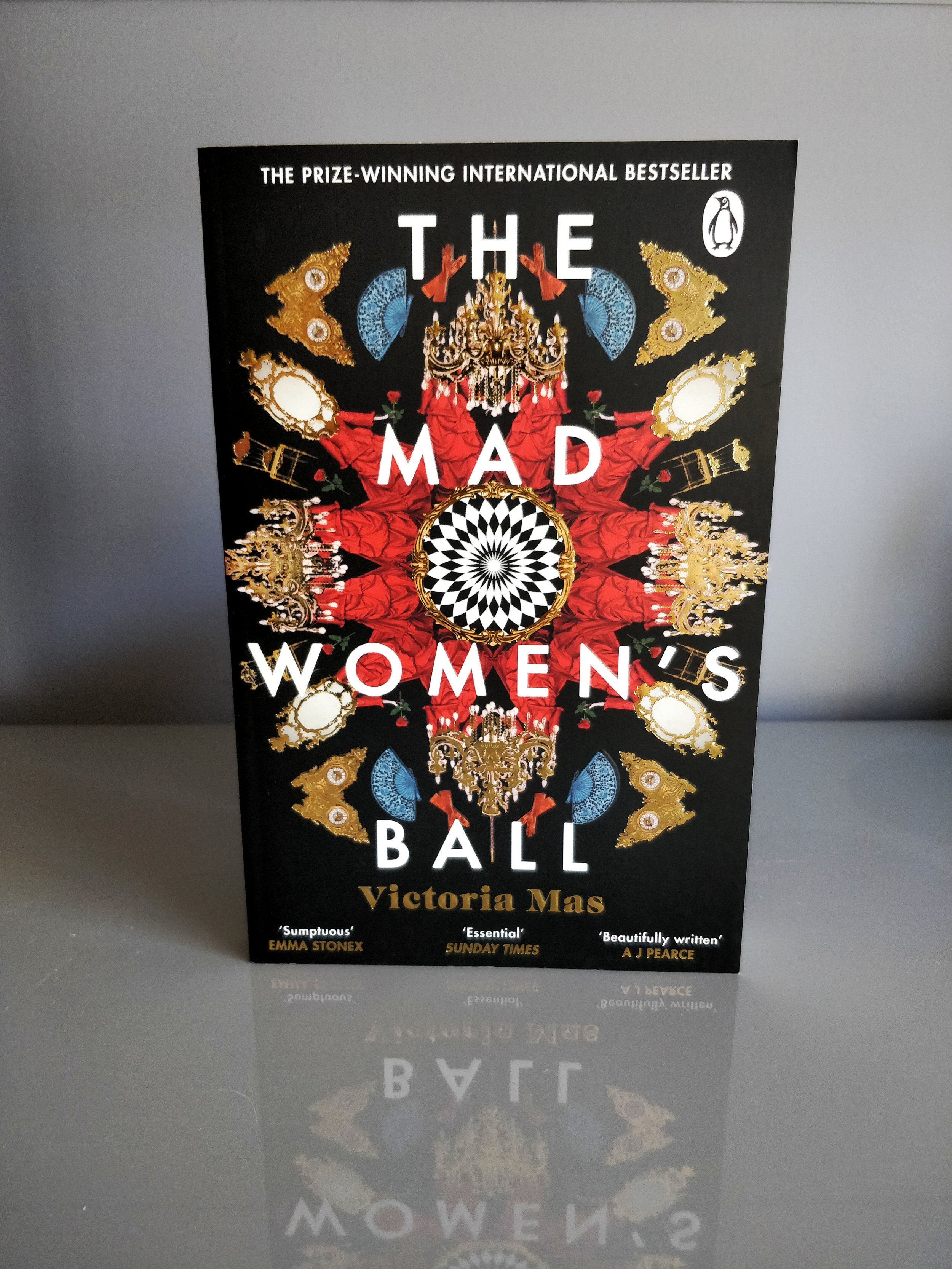

The Mad Women’s Ball by Victoria Mas, translated by Frank Wynne

Yes, this first one is translated by a man but for this initiative it only needs to be one or the other.

In this story we are in Paris in the 1800s at the Salpetriere Asylum at which Doctor Charcot practices hypnotism, among other treatments on the women committed. Once a year, he holds a ball for the Parisian elite to come and dance with the patients and essentially treating the women like animals in a zoo.

It is an amazing historical novel looking at the reasons women were placed in such facilities by the men in their lives or by society. It is an incredibly short book, possibly even considered a novella but it is absolutely one of the best books I read in 2022.

Kim Ji-young, Born 1982 by Cho Nam-Joo, translated by Jamie Chang

Considering this is a book that is about a woman from South Korea, facing mysogyny and institutional oppression and the depression that follows, this book is absolutely riveting. I could not put it down and I would liken it to a thriller in its use of language and the way it flows. I was absolutely glued to it from the moment I picked it up until the moment it ended.

Tentacle by Rita Indiana, translated by Achy Obejas

The blurb describes this as “an electric novel with a big appetite and a brave vision, plunging headfirst into questions of climate change, technology, Yoruba ritual, queer politics, poverty, sex, colonialism and contemporary art. Bursting with punk energy and lyricism, it's a restless, addictive trip: The Tempest meets the telenovela.”

Is that not the most intriguing blurb you’ve ever read? This is another deceptively short novel. As you are reading it, it seems there are so many strands and aspects to the story and you cannot imagine how they are going to come together within the low page count but Indiana achieves it. I don’t think this is as enjoyable a read as the previous two books I mentioned but I haven’t been able to stop thinking about this book and I really want to reread it soon so I had to include it.

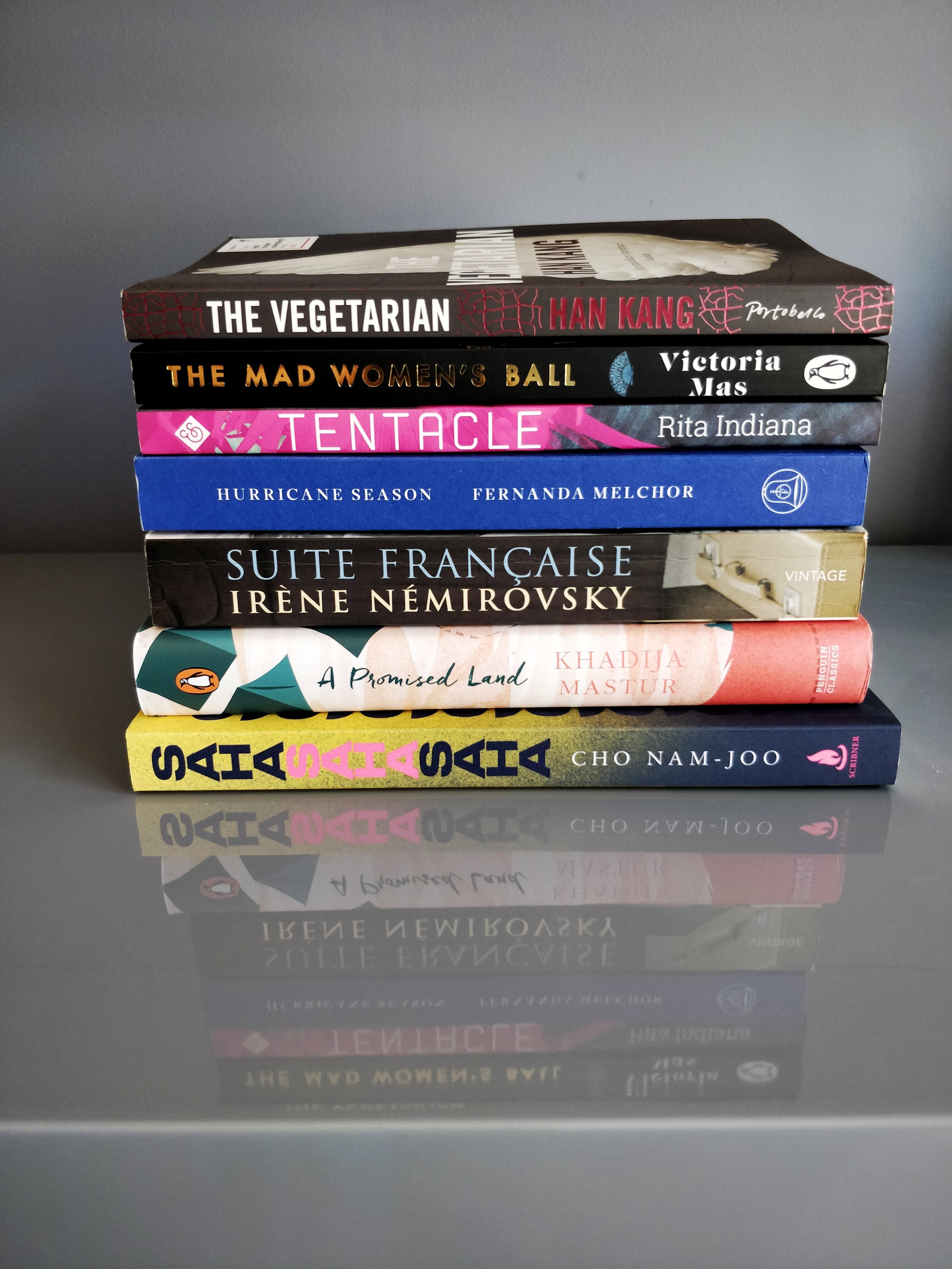

My 2023 reads

I won’t go into detail on any of these books as I will review them at the end of the month/early next month once I have read them but here are the books that I have picked out for myself:

The Memory Police by Yoko Ogawa, translated by Stephen Snyder

The Vegetarian by Han Kang, translated by Deborah Smith

Fieldwork in Ukrainian Sex by Oksana Zabuzhko, translated by Halyna Hryn

Saha by Cho Nam-Joo, translated by Jamie Chang

Hurricane Season by Fernanda Melchor, translated by Sophie Hughes

*The books mentioned in this post contain affiliate links with Bookshop.org. Bookshop.org is an alternative affiliate program to Amazon which awards a small commission to both the creator (me) and to independent bookshops. If you decide to buy any of the books mentioned in this post, please consider purchasing them through the links as it helps me and keeps money away from Amazon.

Bibliography for essay extract:

Barthes, R. (1968) The Death of the Author. Available at http://mariabuszek.com/mariabuszek/kcai/PoMoSeminar/Readings/BarthesAuthor.pdf

Cooke, R (2016) The Subtle Art of Translating Foreign Fiction. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2016/jul/24/subtle-art-of-translating-foreign-fiction-ferrante-knausgaard (Accessed April 27, 2023).

Venuti, L. (2019) Rethinking Translation: Discourse, Subjectivity, Ideology. Abingdon: Routledge.

Walker, C. (1991) "Persona Criticism and the Death of the Author," in W.H. Epstein (ed) Contesting the Subject: Essays in the Postmodern Theory and Practice of Biography and Biographical Criticism. West Lafayette: Purdue University Press, pp. 109 - 120